Currently, one of the biggest things our society and media suffer from is a lack of nuance. We can see this playing out in the current debate around the labor shortage.

There are two predominant, opposing views on the labor shortage:

- “People are lazy *ssholes and don’t want to work, especially when the government will pay them not to.”

- “People deserve to be paid more, and they’re walking away from work until they’re fairly compensated.”

These two views each have some truth to them, but the overall dichotomy is a false one that is causing people to miss the forest for the trees. The two arguments above are a perfect example of an overly simplified dialectic composed of pre-packaged ideologies handed down to us from mainstream media. Thus, the debate between each side is about as interesting as Republican vs. Democrat, or Coke vs. Pepsi, or the menagerie of other largely meaningless debates that occupy 95% of mainstream culture.

Below, I hope to provide you with a more nuanced look at the deeper forces underlying changes in the labor market at a more foundational level. These are forces that have been in motion for decades, and thus have immense momentum behind them. I think they can provide a much more nuanced understanding of a complex issue compared to the two pre-packaged, ideological stances above, which have more to do with people toeing their party line.

Reason #1: Declining Demographics & Birthrates

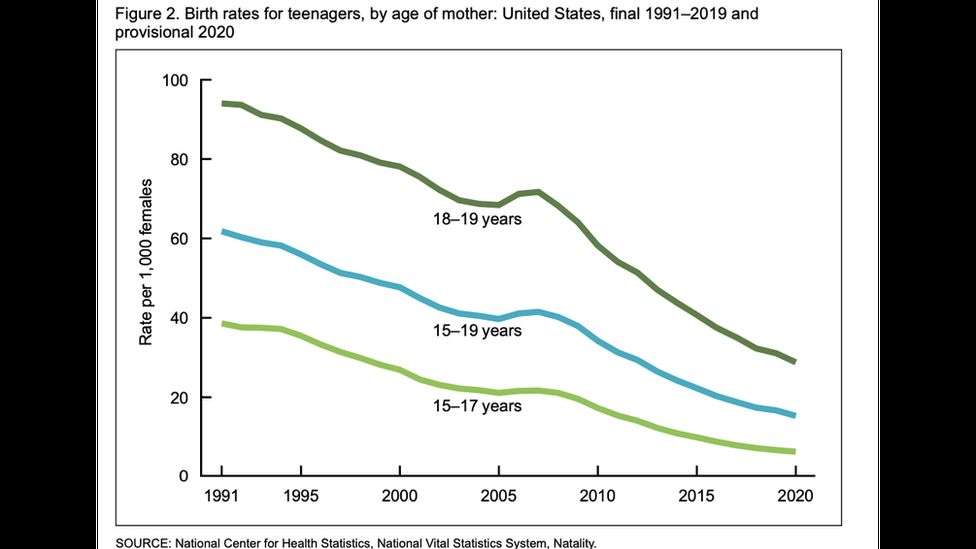

Birthrates in western, industrialized countries have been declining for decades now, with 2021 bringing the US birthrate to its lowest point ever. We don’t hear much outcry over this, as most people presume the world is over-populated. It’s often supposed that if there are fewer births, we’ll see less strain on the planet and less competition for food and natural resources. Overall that sounds like a pretty good thing, right?

While such a view has some truth, it’s still an overly simplistic stance that glazes over important consequences of the trend. For instance: how these falling birthrates may effect the labor market.

We’re now seeing particularly sharp shortages in the service industry and a failure to fill entry-level roles across sectors. These are typically positions held by younger people – a demographic that is in increasingly short supply.

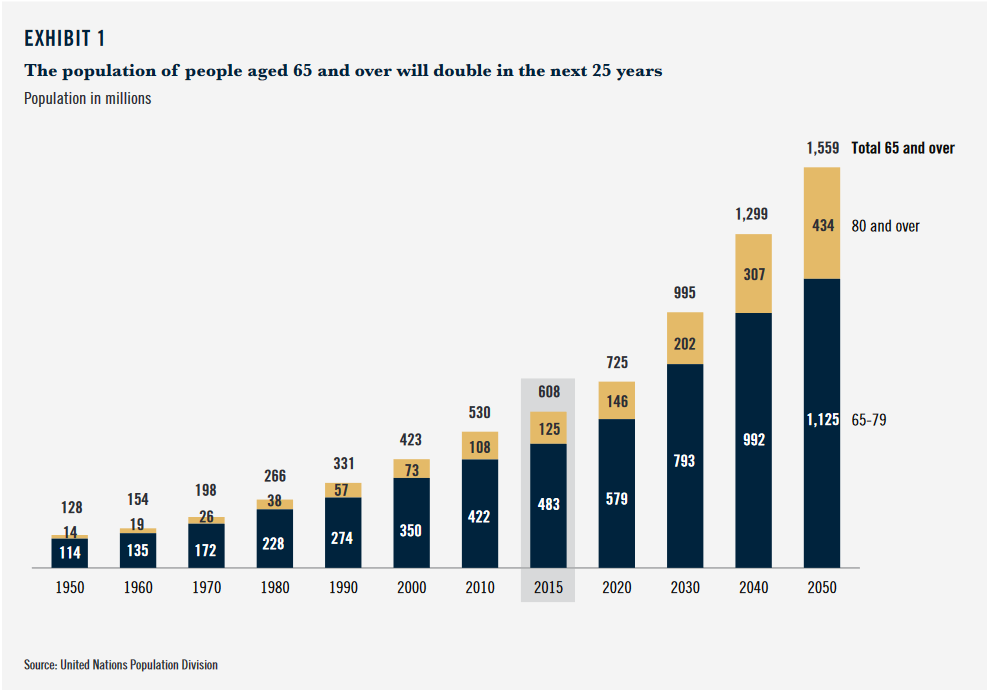

Not only are fewer younger people coming online and subsequently joining the workforce, our population is also ageing rapidly, meaning there will be a surge in retirees continuing to walk away from their long-held positions (which would explain why we’re also seeing shortages in skilled labor):

Looking at the labor shortage as a demographic issue also may also explain why, so far, economic incentive programs aren’t working. An incentive program in Montana “designed to provide bonuses to Montanans who returned to the workforce” is now likely to pay out just one-third of the funds that were allocated to it. If the issue is a lack of young people and a surge in retirees, no amount of higher pay is going to fix the problem.

If you live in the United States, you can probably see anecdotal evidence for demographic trends in the workforce in your own day-to-day life. The next time you go to a grocery store, fast food place, gas station, etc, observe the age of the people working there. These are positions you’d expect to be predominantly staffed by young people just entering the workforce. Yet due to the trends discussed above, many of these service roles in my area (and probably in yours) are now largely staffed by people middle-aged or older.

Reason #2: A Male Exodus from Work, School & Marriage

Men are disappearing in record numbers – not just from the labor market, but also from school and marriage.

The Wall Street Journal recently published two articles on men’s disappearance from college specifically:

- A Generation of American Men Give Up on College: ‘I Just Feel Lost’

- Why Men Are Disappearing on Campus

As usual, the social scientists in each article hone in on the common scape goats. Men are disappearing because of video games and porn, they say. Ironically, such a stance is markedly similar to that of Jordan Peterson, who all leftist social scientists claim to hate, and whose profound advice to men usually includes trying harder and cleaning one’s room.

I think a far more likely and nuanced reason for men’s disappearance is actually these three trends themselves (men leaving work, school, and marriage) and the interrelated effect they exert upon one another. Let me explain.

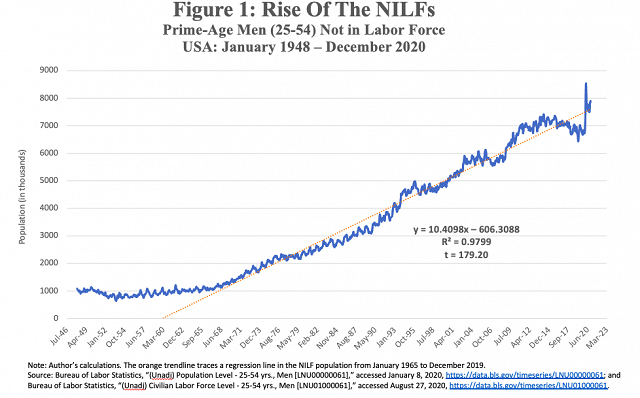

First, the two WSJ articles above make it clear that more and more young men are opting not to attend college. Whether this is due to the macroeconomic climate, or the political climate on college campuses can be debated. But one thing is clear: the trend is resulting in less men subsequently entering the workforce. This is simply because men with college degrees are more likely to participate in the workforce than those without degrees.

There is a very clear correlation between education levels and labor force participation rates:

/media/img/posts/2019/03/Screen_Shot_2019_03_08_at_12.52.50_PM/original.png)

Thus it should come as no surprise that the amount of prime age “NILF” (Not In the Labor Force) men has exploded over the past two decades, just as college attendance for men has simultaneously declined:

We then have another wrench, or trend, to throw into the mix, which is falling marriage rates across both genders – again, a force that has been in motion for decades:

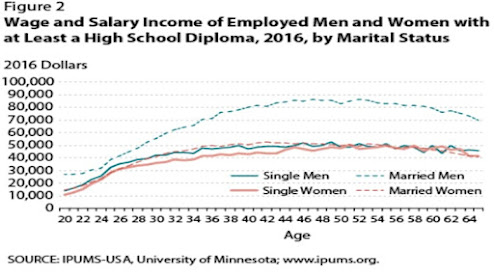

I argue that these three trends form a feedback loop that acts to further accelerate one another. Consider: men that aren’t married don’t need as much income. Thus, they don’t need to work as much, as long, or as hard as a married man. Thus, unmarried men can more easily opt out of the workforce. Given this line of reasoning, the strong correlation we see between rising numbers of NILF men and declining numbers of married men is also pretty understandable.

Of course, that doesn’t help explain men’s falling participation in college. But it might if we look at it this way: perhaps a large percentage of these college-aged men have no interest in being married, or having kids, or at least not for many years down the line (the age of those who still do get married or have kids has been steadily rising). If a man knows this from the start, he loses much of the economic incentive to go to college.

As a young single guy myself, with young single male friends, I can tell you that almost none of us have expenses upwards of, say, $2000 USD a month. For men with roommates, or who live at home, the number is far lower than even that.

So why does a single man, with little prospect of getting married in the future, need to work a full time high powered career, the type of career you’d go to college or graduate school for? He doesn’t. If his expenses are $2K/month, he could make 60K/year working a trade and save over 50% of his income each year. In fact, even if he made 40K/year he could likely save a greater percentage of his income than the average American saves (13.7%) if he desired to do so.

Of course, these are rough, arbitrary figures, but I’m using them to illustrate a simple yet important point: a nation of single men without marriage prospects is not incentivized to work very hard.

The statistics bear this out. Married men are the highest income earners, and single men earn nearly 40% less than them:

I hope I am succeeding in making this a statistical, rather than political argument. I think it is irresponsible to claim that video games or government economic incentives are the culprits for the trends laid out above. Such things surely do play a role, but it’s a very small one.

The larger, more important forces at work include things like a rise in unmarried men, which means a drop in the nation’s highest income earners and producers of GDP. Unmarried men are not incentivized to work as much, so we also see rising numbers of NILF men who are not participating in the workforce at all. Single men who don’t plan to get married any time soon are also not incentivized to bring home a high income, so they are also not incentivized to go into extraordinary debt to earn a college degree.

One could also argue that the cycle works in reverse: the growth of NILF and non-college educated men creates a “lack of economically attractive men” for women to marry – lowering marriage rates further, and creating a feedback loop that further accelerates all of these trends.

Bottom Line

In short: the real reason for the labor shortage is not because “people are lazy and want their gimmes” or even because people want higher pay from their employers. This is only a very small part of what we see playing out. Declining demographics and labor participation rates have been in motion for decades, and are getting worse due to the acceleration of deeply interrelated, fundamental social trends like those highlighted above.

Want to Go Deeper?

If you enjoyed the ideas in this piece and want to go further down the rabbit hole, there are some books you might like.

Some ideas in this article were influenced by the following books:

- Brave New World – By Aldous Huxley

Huxley’s magnum opus reveals a dystopian future without romance or families, where “everyone belongs to everyone else.” Children are created in test tubes and immediately conditioned by the state to fill specific roles in society.

- Men Without Work – By Nicholas Eberstadt

Eberstadt explores the consistent decline in male labor participation that we’ve seen since the 1950s. He focuses particularly on prime age NILF (Not In the Labor Force) men (age 25 – 54 years old).

- Atlas Shrugged – By Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand’s final novel explores what the world would look like if the most competent, productive and creative people turn their back on the workforce and society at large.

- Children of Men – 2006 Movie, 1992 Novel by PD James

Based off the PD James novel of the same name, this science fiction thriller movie takes place in a world where infertility threatens mankind with extinction and the last child born has perished.